The 85+ Year Old CTF: D’Agapeyeff Cipher

I’ve been reading the dictionary in my free time…?

Published 9/10/2021. Updated 12/2022, edited slightly in 01/2025.

Cipher Discovery

One night while browsing Wikipedia’s List of Unsolved Problems I stumbled across an interesting page - List of ciphertexts. A lot of the information on the page wasn’t particularly new to me: Beale, Enigma, Kryptos, etc.

But one did catch my eye that I had not heard of -

| Year of origin | Ciphertext | Decipherment status |

|---|---|---|

| 1939 | D’Agapeyeff Cipher | Unsolved |

An unsolved 20th century cipher? For the last 80+ years? That’s interesting…

The D’Agapeyeff cipher is an as-yet unbroken cipher that appears in the first edition of Codes and Ciphers, an elementary book on cryptography published by the Russian-born English cryptographer and cartographer Alexander D’Agapeyeff in 1939.

Offered as a “challenge cipher” at the end of the book, the ciphertext is:

75628 28591 62916 48164 91748 58464 74748 28483 81638 18174 74826 26475 83828 49175 74658 37575 75936 36565 81638 17585 75756 46282 92857 46382 75748 38165 81848 56485 64858 56382 72628 36281 81728 16463 75828 16483 63828 58163 63630 47481 91918 46385 84656 48565 62946 26285 91859 17491 72756 46575 71658 36264 74818 28462 82649 18193 65626 48484 91838 57491 81657 27483 83858 28364 62726 26562 83759 27263 82827 27283 82858 47582 81837 28462 82837 58164 75748 58162 92000

An ELEMENTARY book? That doesn’t add up. I had to check this out myself.

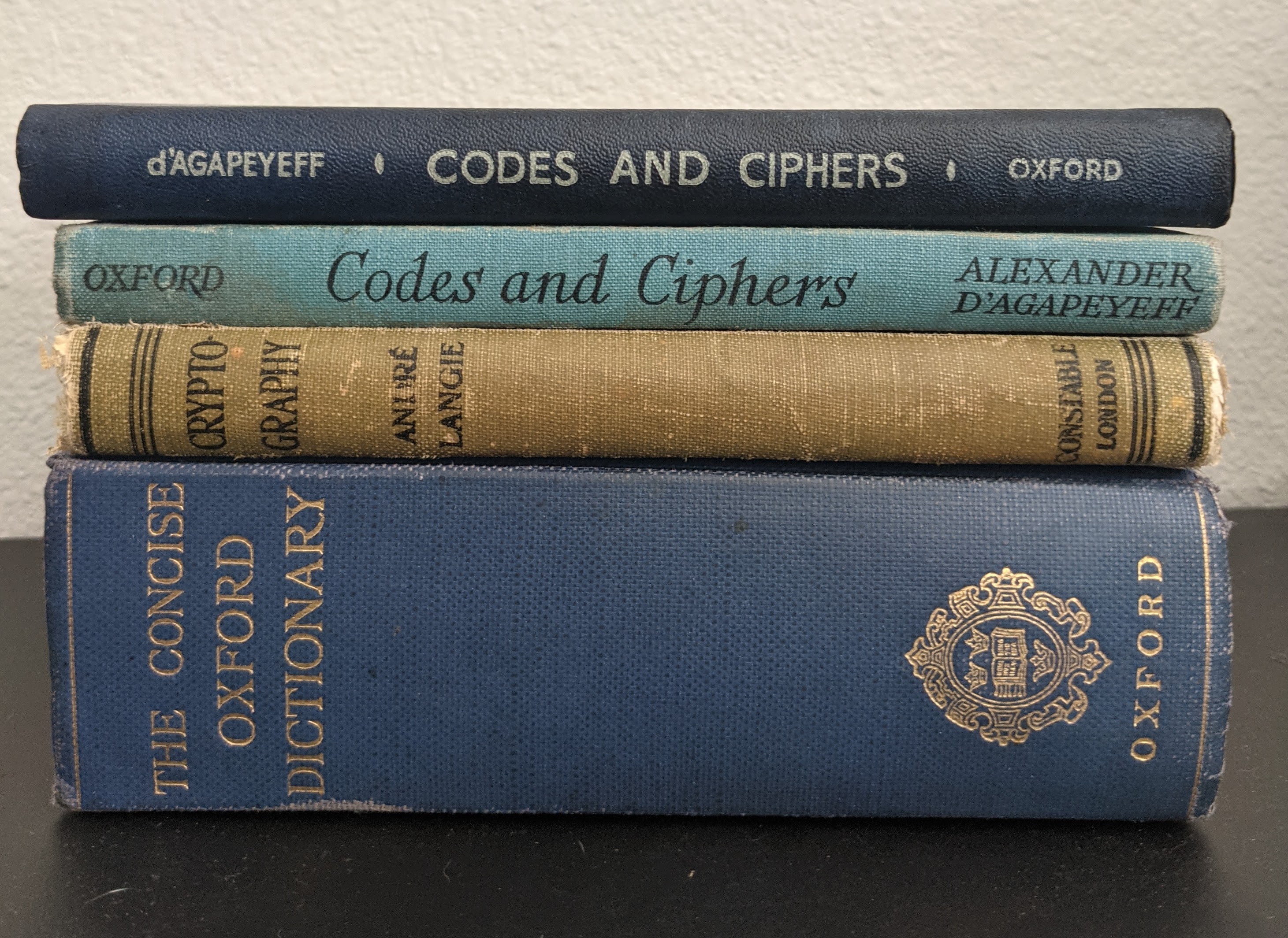

That seems lame. Let’s go for the original - the 1st edition. Thanks, ebay.

It’s a really neat book. Especially for a Cyber/Cipher nerd like myself. Even if I’m not a particularly talented or well-versed cryptologist.

It even has that musky, mildly sweet-organic decomposition scent that books seem to develop over time.

I spent more time smelling it than I’d like to admit.

“He Forgot”

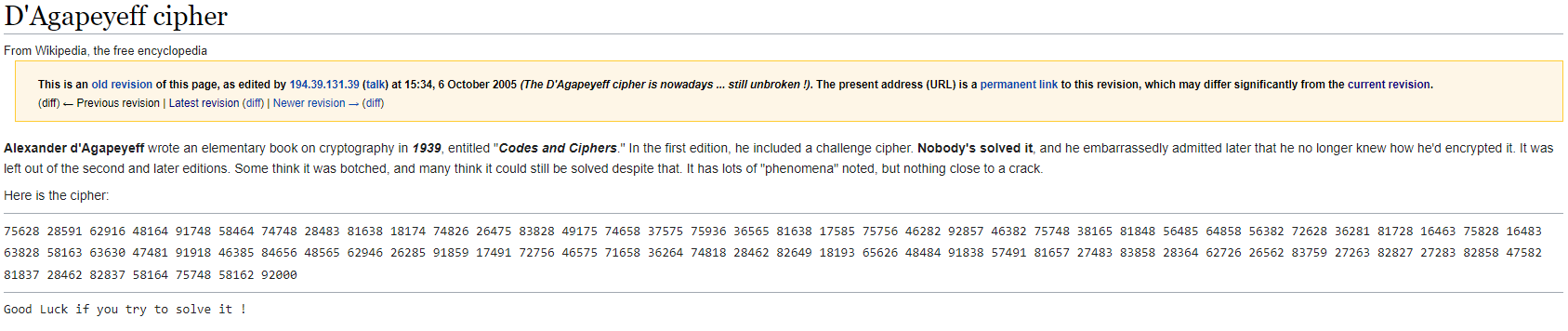

One of the first things you’ll see on the wikipedia page is this interesting quote

It was not included in later editions, and D’Agapeyeff is said to have admitted later to having forgotten how he had encrypted it.

Literally just about any blog online seems to mention this or other vague “quotes” online regarding D’Agapeyeff’s son “remembering him being very embarrassed that he had forgotten how to solve it” or some other variation of this.

Many use this as proof that the cipher is unsolvable. However, in all my research I couldn not actually find a source for this quote. Not even Wikipedia has a reference (A classic Wikipedia problem!).

This reference also dates back all the way to the first Wikipedia entry for the cipher in 2005

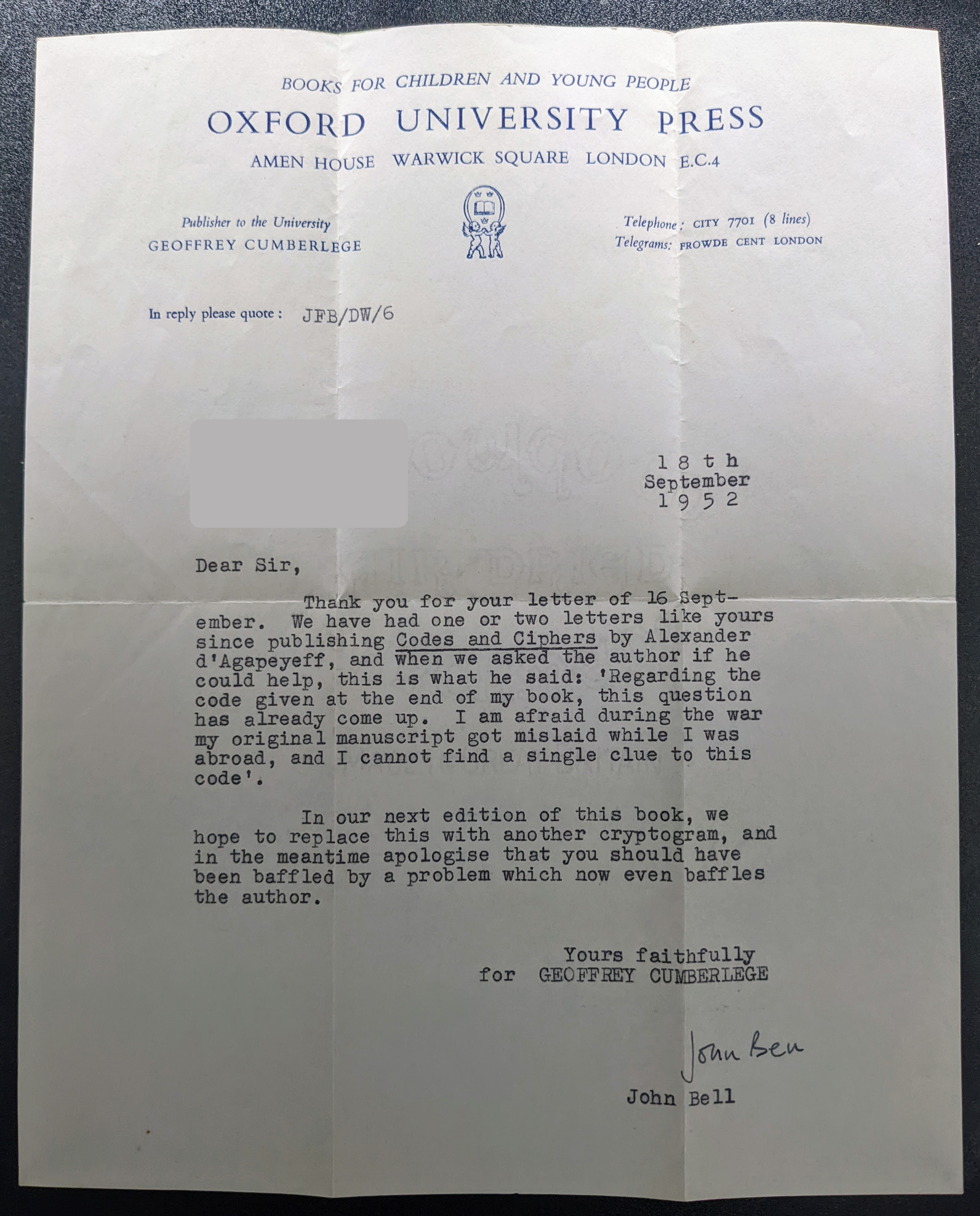

In 2021 when I first published this blog this bugged me. Thankfully, after 2 years of on/off searching and a bit of luck (maybe a lot of luck) I believe I am now the proud owner of a source

A letter from September 18th, 1952 with a second hand quote from the books publisher confirming this quote from DA basically admitting that he has indeed forgotten and lost his solution while traveling. This letter was found in a copy of Mansfield’s “The Solution of Codes and Ciphers” and thankfully the seller was kind enough to include the forgotten bookmark with the sale of the book!

I did edit the letter - I felt weird about putting someone’s address on the internet, even if it was from 1952. As far as I can tell, this quote from D’A is not printed anywhere else on the internet. Alas, after many years I could provide an actual (second hand) citation for the mysterious Wikipedia sentence about a forgotten solution. I do wish the letter was dated closer to 1939, but 1952 will do and aligns nicely with the removal of the cipher from the edition printed that same year.

Okay, so…

So he forgot…but does that mean it’s impossible ? Hard to say of course, but for the sake of this post and for FUN let’s not assume it’s impossible.

For the sake of this post, let’s assume D’A was not a complete dummy - he actually did create valid plaintext, and encrypted it with one or more known encryption/encipherment methods for the era (1939). Furthermore, on page 145 of the 1939 edition he warns

It is very common in deciphering to come across mistakes … by the encipherer …

Would he include a challenge cipher without solving it once himself to prove it was mistake free? I mean, maybe - I don’t know? Was a mistake added on purpose to increase the challenge? Did he not even realize his mistake and somehow “solve” it in a proof-check while incorporating his same mistake twice? Again, maybe…

Did he superencipher this thing so hard that he immediately forgot how he even did it without his notes? Guess so…if anyone stumbles across an old piece of paper somewhere in Europe with the long sought solution this on it please let me know?

Unfortunately there were no cloud storage providers in 1939. Paper is lost, soiled, destroyed, etc.

DA passed away at the surprisingly young age of 52 (1902 -> 1955) leaving behind no known additional hints. Worst case scenario he setup the whole thing as a one-time pad for a laugh. I have read some sources online that claim it was possibly added as a “hoax” but somehow, on the eve of WWII, I don’t think D’Agapaffeye was in a joking mood. Especially with the topic of ciphers being exponentially more relevant on the world stage.

General Cipher Analysis

The cipher is delimited into numeric groups of 5 digits (patristocrat form).

75628 28591 62916 48164 91748 58464 74748 28483 81638 18174

74826 26475 83828 49175 74658 37575 75936 36565 81638 17585

75756 46282 92857 46382 75748 38165 81848 56485 64858 56382

72628 36281 81728 16463 75828 16483 63828 58163 63630 47481

91918 46385 84656 48565 62946 26285 91859 17491 72756 46575

71658 36264 74818 28462 82649 18193 65626 48484 91838 57491

81657 27483 83858 28364 62726 26562 83759 27263 82827 27283

82858 47582 81837 28462 82837 58164 75748 58162 92000

All said, there’s 79 groups in an 8x10 grid with the final 5 digit grouping missing. That makes 395 individual digits.

Here’s a frequency analysis of the 5 digit groupings where count > 1

| 5 Digit Sequence: | 81638 | 75748 | 28462 | * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency: | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

But more realistically, this needs to be broken down into digraphs (pairs) and we can do a better frequency analysis.

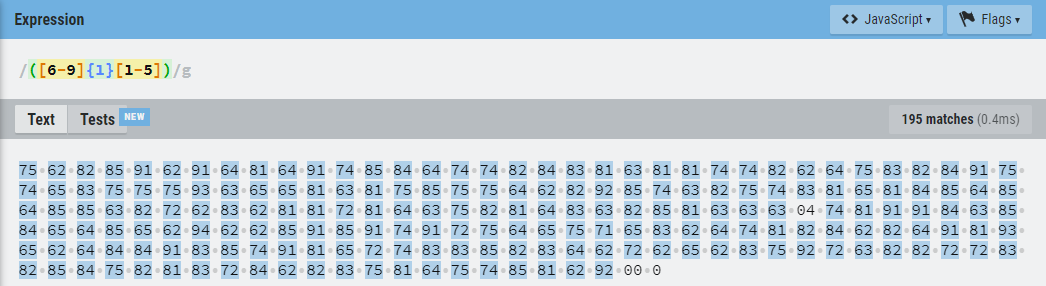

75 62 82 85 91 62 91 64 81 64 91 74 85 84 64 74 74 82 84 83 81 63 81 81 74 74 82 62 64 75 83 82 84 91 75 74 65 83 75 75 75 93 63 65 65 81 63 81 75 85 75 75 64 62 82 92 85 74 63 82 75 74 83 81 65 81 84 85 64 85 64 85 85 63 82 72 62 83 62 81 81 72 81 64 63 75 82 81 64 83 63 82 85 81 63 63 63 04 74 81 91 91 84 63 85 84 65 64 85 65 62 94 62 62 85 91 85 91 74 91 72 75 64 65 75 71 65 83 62 64 74 81 82 84 62 82 64 91 81 93 65 62 64 84 84 91 83 85 74 91 81 65 72 74 83 83 85 82 83 64 62 72 62 65 62 83 75 92 72 63 82 82 72 72 83 82 85 84 75 82 81 83 72 84 62 82 83 75 81 64 75 74 85 81 62 92 00 0

| Digit Pair | 81 | 75, 62, 82, 85 | 64 | 83 | 74 | 63, 91 | 84, 65 | 72 | 92 | 93 | 04, 94,71,00,0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency: | 20 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Breaking the pairs down further for frequency of each digit pair:

| First Digit | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | Second Digit | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency: | 56 | 41 | 80 | 18 | 3 | Frequency: | 33 | 46 | 29 | 43 | 5 | 1 |

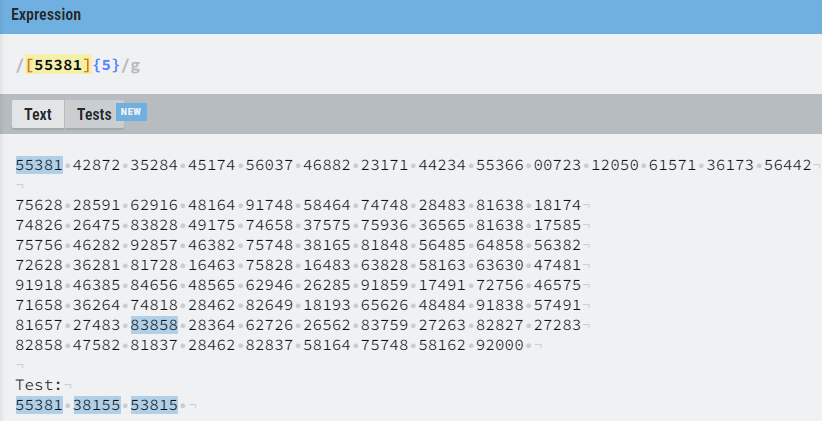

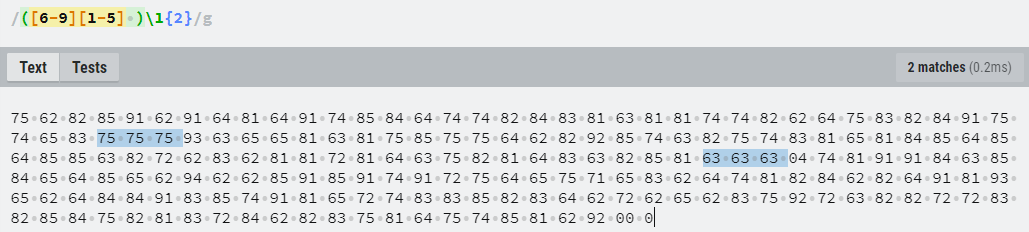

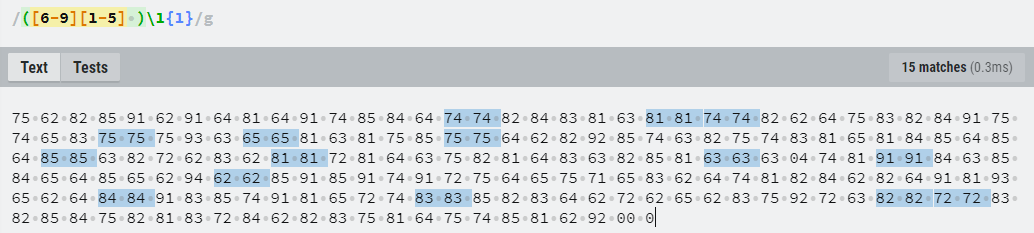

With the exception of 0, there is no overlap between first and second digits. Here’s what that looks like with a regex applied. Certainly weird, with the only outliers being: 04, 00, 0

Triplets:

Doublets:

This 14x14 grid (technically there’s a spare row of 0’s…) is a popular analysis tool. This is because if you discard the last three 0’s as “null” values, you have 192 paired digits which leads to a very convenient 14x14 grid. Padding messages with 0’s was also a common practice of the era for telegraph messages.

This grid has a green color scale applied from most frequent character, to least, with the top ten values having decreasing shades of green until the bottom frequency values all end near-white.

This method is also vaguely supported by this snippet on page 127

Numeral … Ciphers … letters are replaced by numbers…A,B,C,D may stand for any numbers (preferably double) from 10 to 99.

| 00 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | 75 | 62 | 82 | 85 | 91 | 62 | 91 | 64 | 81 | 64 | 91 | 74 | 85 | 84 |

| 01 | 64 | 74 | 74 | 82 | 84 | 83 | 81 | 63 | 81 | 81 | 74 | 74 | 82 | 62 |

| 02 | 64 | 75 | 83 | 82 | 84 | 91 | 75 | 74 | 65 | 83 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 93 |

| 03 | 63 | 65 | 65 | 81 | 63 | 81 | 75 | 85 | 75 | 75 | 64 | 62 | 82 | 92 |

| 04 | 85 | 74 | 63 | 82 | 75 | 74 | 83 | 81 | 65 | 81 | 84 | 85 | 64 | 85 |

| 05 | 64 | 85 | 85 | 63 | 82 | 72 | 62 | 83 | 62 | 81 | 81 | 72 | 81 | 64 |

| 06 | 63 | 75 | 82 | 81 | 64 | 83 | 63 | 82 | 85 | 81 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 04 |

| 07 | 74 | 81 | 91 | 91 | 84 | 63 | 85 | 84 | 65 | 64 | 85 | 65 | 62 | 94 |

| 08 | 62 | 62 | 85 | 91 | 85 | 91 | 74 | 91 | 72 | 75 | 64 | 65 | 75 | 71 |

| 09 | 65 | 83 | 62 | 64 | 74 | 81 | 82 | 84 | 62 | 82 | 64 | 91 | 81 | 93 |

| 10 | 65 | 62 | 64 | 84 | 84 | 91 | 83 | 85 | 74 | 91 | 81 | 65 | 72 | 74 |

| 11 | 83 | 83 | 85 | 82 | 83 | 64 | 62 | 72 | 62 | 65 | 62 | 83 | 75 | 92 |

| 12 | 72 | 63 | 82 | 82 | 72 | 72 | 83 | 82 | 85 | 84 | 75 | 82 | 81 | 83 |

| 14 | 72 | 84 | 62 | 82 | 83 | 75 | 81 | 64 | 75 | 74 | 85 | 81 | 62 | 92 |

| 15 | 00 | 0 |

The triplet sets highlighted in red are interesting from a frequency standpoint…otherwise there are several pairs of pairs within the set and not worth highlighting. The “spare” row of 0’s is probably safe to ignore but including it doesn’t hurt for now.

Initial Possibilities

After some analysis and reading the book itself it seems to me the possible cipher may be:

- Book Cipher

- Numeric codes align to page/line/word or letter within a given text

- Discussed toward the end of the book, aligns nicely with the final unsolved challenge cipher and even looks a bit like the examples given

- What book? The book itself or the dictionary mentioned in the text?

- On page 127 D’A calls these “highly specialized forms of substitution”

- Substituted Transpostion

- So many permutations with this…really difficult, but often referenced with D’A analysis online

- Other Ciphers

- Nihillist Cipher

- Is a numeric based symmetric key cipher

- If you load the cipher into CryptoCrack the initial analysis points to possible Nhillist

- Background -

- D’A was born in Russia…maybe this is a nationalistic callback for him?

- The dust jacket states “D’Agapeyeff was an intelligence officer in the First World War…in the Baltic until 1921 where he gained a knowledge of espionage and counter-espionage activities between Germany and Russia

- Mirabeau Cipher

- A strange lack of information regarding this cipher on the web. Supposedly, this french guy used a simple numeric substitution system involving grouping seemingly arbitrary letters into groups of 5 and assigning a group # of a letter # within the group to create two digit pairs which were then sent out as the cipher.

- Vigenère

- D’A was in WWI? Maybe ADFGVX?

- MONOME-DINOME seems vaguely numeric looking…

- Polybius Squares, Bifid, Trifid, Tap Codes, Tridigital, Morbit, Rail fence, Porta, Ubchi…etc.

- Honestly, it’s anyone’s guess.

- Nihillist Cipher

A few disadvantages with these more obscure ciphers is that they are not mentioned in the book. So without the modern advantage of wikipedia and the internet it’s difficult to know if D’A would even know of their existence? Digging through the references in the book itself we can find other books he probably read as research, so if a cipher is mentioned there it’s possible.

Some outstanding questions:

- Should we “keep” the intervals of 5 digits or accept the 2-digit pairings and discard the 0’s?

- What about 04? 04 is “distinct” from the 000 at the end in some ways.

- What structure forms the interesting 6-9/1-5 pattern we see in the two digit pairs?

Dictionary (Book) Cipher

One of the more obvious suggestions from the book is to use an actual dictionary to map the number of words to the sequence. However, to me, although I have looked into book ciphers more than I should probably admit the fundamental flaw with these approaches is this – how on earth would D’A have FORGOTTEN this? I feel like the scenario of “I have forgotten my complicated substitution/transposition cipher” is fairly reasonable but forgetting “Oh right I was counting a bunch of words in THE DICTIONARY” is a lot more … memorable? Now of course, D’A could have just been lying to everyone about having “Forgotten” and he knew all along it was THE DICTIONARY but…I’m just not sure (and neither are you, okay???)

Anyways, we can look at it all the same. In this case, the highest number in the sequence is 92857 and the lowest is 16463.

And on page #129

One of the ways in which ordinary dictionaries can be used is first to agree on a certain edition, say, for instance, the Concise Oxford Dictionary, current edition, by Fowler and Le Mesurier…

This could explain why the ciper was apparently removed from the book in 1952. The concise oxford english dictionary 3rd edition came out in 1934, and was updated to 4th edition in 1951. Hm…well we’re going to need a dictionary from 1934-1939? That’s not ideal…

ebay? Yep - $9.

So this dictionary from 1938 is a mere 1507 pages long. Well that certainly qualifies for our 5 digit number pairs, right? Unfortunately, the individual words are not numbered.

Let’s take the same approach as before.

75628 28591 ... 92000

Houston, we have a problem. There’s no way this 1500 page book has over 90,000 words in it.

As noted in the book, page #154

Even in the largest dictionaries 60,000 to 65,000 words are quite common.

Assuming calling out this “concise” version of the dictionary was on purpose, why do we have so many numbers above 65 in our unsolved cipher? 62, 63, 64, 65, 72, 75, 81, 82, 83, 84, 91, 92…well over half the cipher leads with digit pairs beyond the scope of this dictionary.

Page 153

… Mr. Mansfield … calculated dictionary progressive lists, giving numbers of words beginning with any two letters in dictionaries of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, and 100 thousand words.

Hold up, a dictionary with 100,000 words? That would cover my 92000 problem. Were there dictionaries in the 1930s that had 100,000 words in them? Seems like the answer is obviously. So is the “clue” simply that you need a dictionary with 100k words?

hm…

Okay, I literally have to stop spending money on ebay. Maybe I can convince my wife they’re for decoration in the living room as “Vintage” books? Blue matches the uh…wall…paint?

Okay, I literally have to stop spending money on ebay. Maybe I can convince my wife they’re for decoration in the living room as “Vintage” books? Blue matches the uh…wall…paint?

So hypothetically, even if I bought this $100 dictionary…what would I find? Words, presumably. However, I have no intention of counting nearly 100,000 words by hand.

Maybe we can do what Mr. Mansfield did and use some statistics. If there are ~100k words in the book, and I was to go to word 92000, where would be be in the Alphabet? X? Y? Z?

I know the frequency of characters in english words, but is there a different frequency for the letters that start words? Eg. There’s a lot of the letter “E” in the English language, but are there that many words that start with the letter “E”? First letter frequency?

Thank God For Wikipedia. Turns out, no. While “E” is the most common letter in a word (13%), “T” is the most common first letter in a word (17%). However, in dictionaries, the most common letter is “S” (11%). Weird facts but it makes sense that a dictionary would contain lots of words that are not really part of the “lexicon” most people use.

So with this, can I perform a very rough mathematical model for a dictionary of 100,000 words? Sure.

A would be 5700 / 100000 words

B would be 6000 / 100000 words

C would be 9400 / 100000 words

...

X would be 50 / 100000 words

Y would be 360 / 100000 words

Z would be 240 / 100000 words

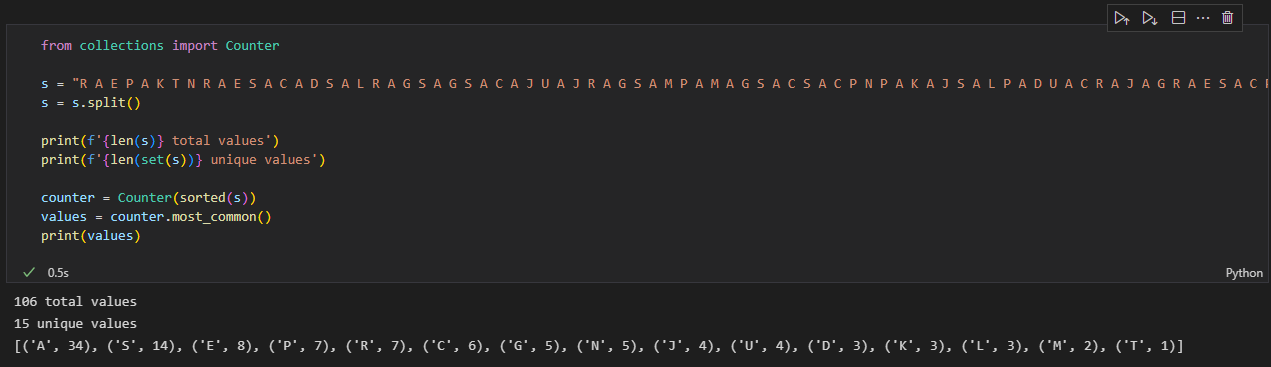

So on and so forth… So, I wrote a script fucntion that takes the % of a first letter word in the dictionary, and maps it to an arbitrary # of words within a dictionary to find the approximate “Letter” for a given range. Then I took the 5 digits providied by the cipher, ran them through the “range finder” and here’s the output:

R A E P A K T N R A

E S A C A D S A L R

A G S A G S A C A J

U A J R A G S A M P

A M A G S A C S A C

P N P A K A J S A L

P A D U A C R A J A

G R A E S A C P A L

U N A E S A E P A D

S A E S A E A K S A

E S N R N U

Well…it’s a start maybe? Seems like a really long cipher if each character here represents the beginning of a whole word.

If it’s not a whole word, but just a literal letter, it certainly doesn’t spell anything right now, plus the frequency of the letter skewed. Could you possibly re-arrange this into a real sentence? Maybe I’ll write a script to try that some other time. It’s also possible this could be swapped over with a simple substitution cipher to get a more accurate alphabet to work with?

Back to the whole word theory - we would need a slightly more accurate range mapping - while the first letter is interesting, having the range also determine the frequency of the second letter would help narrow things down.

It’s good to know that 75628 might be a word starting with “R” but without the second letter its a large pool…I downloaded a random dictionary of about ~25k words from Github, and it came with 1,442 words that start with “R”…far too many to just randomly guess from.

Here’s what that would look like with 100% random words from the dictionary

recommended exercises photographed killer troupe nagging rows ego slightly clockwork reacted duration shoots left robotic gallon superheroes grooming swerving coat residence janitorial unbelievable jackpot regal geography slams metric plaything mistook rebirth governess sandbar corporation skirmishes coals prognosis neglected positioned kitties urgent jasper smith lucky physique drowsy unwarranted cooking ratio jungle ratio gor rustle enact staffers cool pigtails launcher utmost networks saintly evidence super estimates panicked display settle evaporated summers empire sweets knots stardom edges seasoned nixed rehab natured unbalanced

There are no repeating letters, though. These frequencies may be off slightly, if the frequency of first letter words in dictionaries changed over time (1933-2021) which they almost certainly have as new words showed up in the global vocabulary…like yeet.

Plus, who can be bothered to accurately count to 92,000 words? Nobody. Perhaps this cipher has never been solved simply because the solution is too tedious and prone to human decipherment (or encipherment…) error? Unfortunately, online I can’t find anyone who was crazy enough to say “yes, I counted to 92,000 and here’s what I found.”

Realistically, even D’A didn’t do this right? Maybe there’s a copy of a dictionary somewhere with pencil’d in numbers that he used but it seems very far fetched, plus this copy of the dictionary isn’t exactly clear on what you might consider a “word” since dictionaries contain “headwords” and “partial” words for things that end in -ful or -ing, etc…

Book Cipher Continued: Making The Cipher “Fit”

Before we go too deep down the “longer versions of the 1933 dictionary” rabbit hole, can we make the current cipher “fit” into our Concise dictionary instead?

As noted on the wikipedia page, on page 111 D’A says

The cipher is of course easily made out, but if every third, fourth, or fifth letter, as may be previously arranged, is a dummy inserted after a message has been put into cipher, it is then extremely difficult to decipher unless you are in the secret

Okay, so what if we treat some numbers in our cipher text as “Null”? If we assume our dictionary has about ~65k words, then we should look to trim numbers > 6 + maybe that pesky 0?

We can go from this…

75628 28591 62916 48164 91748 58464 74748 28483 81638 18174

74826 26475 83828 49175 74658 37575 75936 36565 81638 17585

75756 46282 92857 46382 75748 38165 81848 56485 64858 56382

72628 36281 81728 16463 75828 16483 63828 58163 63630 47481

91918 46385 84656 48565 62946 26285 91859 17491 72756 46575

71658 36264 74818 28462 82649 18193 65626 48484 91838 57491

81657 27483 83858 28364 62726 26562 83759 27263 82827 27283

82858 47582 81837 28462 82837 58164 75748 58162 92000

To this…

52251 21414 14544 44243 13114

42245 32415 45355 53355 13155

55422 25432 54315 14545 45532

22321 12143 52143 32513 33441

11435 45455 24225 15141 25455

15324 41242 24113 52444 13541

15243 35234 22252 35223 22223

25452 13242 23514 54512 2

The 5x5 column was picked to sort of arbitrarily fit into a polybius square. Well, although it does seem sort of arbitrary to remove so many numbers from the grid it also fits the pattern that we explored with regular expressions earlier.

The neat thing about this arbitrary solution is that you can technically keep the 0’s if you want…

52251 21414 14544 44243 13114

42245 32415 45355 53355 13155

55422 25432 54315 14545 45532

22321 12143 52143 32513 33044

11143 54545 52422 51514 12545

51532 44124 22411 35244 41354

11524 33523 42225 23522 32222

32545 21324 22351 45451 22000

And still have a perfectly organized grid. However, the difference between 5 digit pairs created after entry #14 are significant when shifted by that singular 0, similar to how the difference between word 2 and word 22000 is fairly large. One additional “advantage” of this approach is that the cipher got a lot smaller. Specifically, we go from 79 potential words in the dictionary to 40. No surprises there on the math.

One unfortunate aspect of these two grids is that none of the 5 digit grouping repeat. This is sort of counter to what we might expect when compared to the dictionary cipher provided in the book where 55381 was repeated 5 times (4 times) for “the”.

Regardless, it is possible to have sentences without using the same word twice. Perhaps d’A avoided repeating a simple word like “the” several times to make the cipher more difficult to solve on purpose?

In the book, D’A gives a book cipher example using a dictionary (presumably the concise edition) where he starts by ordering his 5 digit pairs in ascending order, and maps words within the ranges provided (Eg. Word 55381 in the Dictionary) to their associated word pair, perhaps “T”…and then those word pairs, maybe the range associated with “TH” is mapped to the digits 55381, to help build a sentence.

Fortunately…D’Agapeyeff throws us a bone…maybe.

Now we can find in the dictionary the word ‘the’ (55381). This we can count back about twenty words for 55366 (th).

Assuming me and my boy D’A are looking at the same Dictionary, I can confirm that the word “the” shows up on page 1270. If I count back 15 words…I sort of have the same span of words that D’A notes

‘thane’, ‘thank’, ‘that’, ‘thatch’ …

But I think D’A was paraphrasing a bit here, if he was on “the” 55381 and goes back to word 55366 - that’s a difference of 15 words not 4. So my “span” seems reasonable, I end up with words like: thaw, thatch, that, thanksgiving, thankless, thankful, thank, than, thallium, thalamus, etc…all leading up to “-th.” …literally just “th” like he says in the book…which is, depending how you count subdefinitions or variations of words (like thank/thankful) about 15 words away…so maybe this is literally the same version of the dictionary that he was using? That’s a good sign at least?

D’A gives us the solution to the Dictionary Cipher presented

The reconnaissance of the route to the sea has revealed that the aeroplane(s) defensive was over the town.

There’s technically a mistake in this section of the book, which isn’t inspiring. If word 55381 is “the” then why is the 4th position of the cipher 44381 ? And if you literally just count the occurrences of 55381, it only occurs 4 times, not 5. Anyway…

So if 55381 was “The” then 42872 must be “reconnaissance”? That shows up on page 975…but we have a real problem, Houston. I only really noticed after a bit of flipping through the pages.

Great, let’s take our modified “null replaced” cipher and take the groupings of 14 words prior to our “0 conundrum” which are unchanged and see if we can figure them out:

12143,13114,13155,14544,14545,21414,22321,25432,32415,32513,42245,44243,45355,45532,52143,52251,53355,54315,55422

If we take this list, and compare each number to every “known” word/number pair in the already provided solution we can end up with some interesting data.

| Cipher Word | Word Diff | Known Word | Known Word # | Known Word # Page # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52143 | -3223 | that | 55366 | 1269 |

| 52251 | -3115 | that | 55366 | 1269 |

| 32415 | -2869 | of | 35284 | 787 |

| 32513 | -2771 | of | 35284 | 787 |

| 53355 | -2011 | that | 55366 | 1269 |

| 21414 | -1757 | has | 23171 | 526 |

| 54315 | -1051 | that | 55366 | 1269 |

| 22321 | -850 | has | 23171 | 526 |

| 42245 | -627 | reconnaissance | 42872 | 975 |

| 44243 | 9 | revealed | 44234 | 1006 |

| 55422 | 41 | the | 55381 | 1270 |

| 12143 | 93 | defensive | 12050 | 297 |

| 45355 | 181 | route | 45174 | 1030 |

| 45532 | 358 | route | 45174 | 1030 |

| 13114 | 1064 | defensive | 12050 | 297 |

| 13155 | 1105 | defensive | 12050 | 297 |

| 25432 | 2261 | has | 23171 | 526 |

| 14544 | 2494 | defensive | 12050 | 297 |

| 14545 | 2495 | defensive | 12050 | 297 |

In this case, our cipher has the number 44243, and the cipher text solved in the book as an example has word 44234. If we simply count 9 words up from 44234 “975” on page 1006 we should arrive at word 44233. Counting to just 9.

That gives us…

0 reveal(ed)

1 reveille

2 revel

3 revelation

4 revelationist

5 revenant

6 revendication

7 revenge

8 revenue

9 reverberate

10 revere

11 reverence

Depending on how you “count” words you might land on “revenue” or “revenge” which are both interesting. However, we don’t really need to count that exactly, with a seletion of ~10 potential words we could pretty easily brute force solutions until a sentence forms that makes grammatical/logical sense…right?

So counting 9 is easy. However, we still have numbers too large to count accurately. I consider that anything over 500.

Thankfully, we can make some solid estimates, though. Dealing with a maximum of ~3200 words is a lot better than dealing with numbers > 10k. So we can probably start guessing some diphthongs/”probable first two letters” to each of our tables. The farther away from a “known” word we get, the fuzzier our definition may be.

After-all, as D’A says himself on page 156

…application of the law of probability to dictionary codes is very interesting.

I may keep exploring this in the future.

I also bought this other old book…

Yes…ebay, again…

This book was originally published in 1918 by a French author, Andre Langie, under the title of “De la cryptographie; etude sur les ecritures secretes.” and translated in 1922 by a British man named J.C.H. MACBETH.

I mostly just thought it was cool…but it’s also a reference in the bibliography in D’A’s Codes and Ciphers. So I thought I’d read it to see if there was anything interesting. Especially considering it’s one of the more “recent” references (1922) that also happened to be in English.

I mostly just thought it was cool…but it’s also a reference in the bibliography in D’A’s Codes and Ciphers. So I thought I’d read it to see if there was anything interesting. Especially considering it’s one of the more “recent” references (1922) that also happened to be in English.

Turns out I didn’t need to buy it though, since the whole thing is scanned into the internet archive. So you can read it for free!

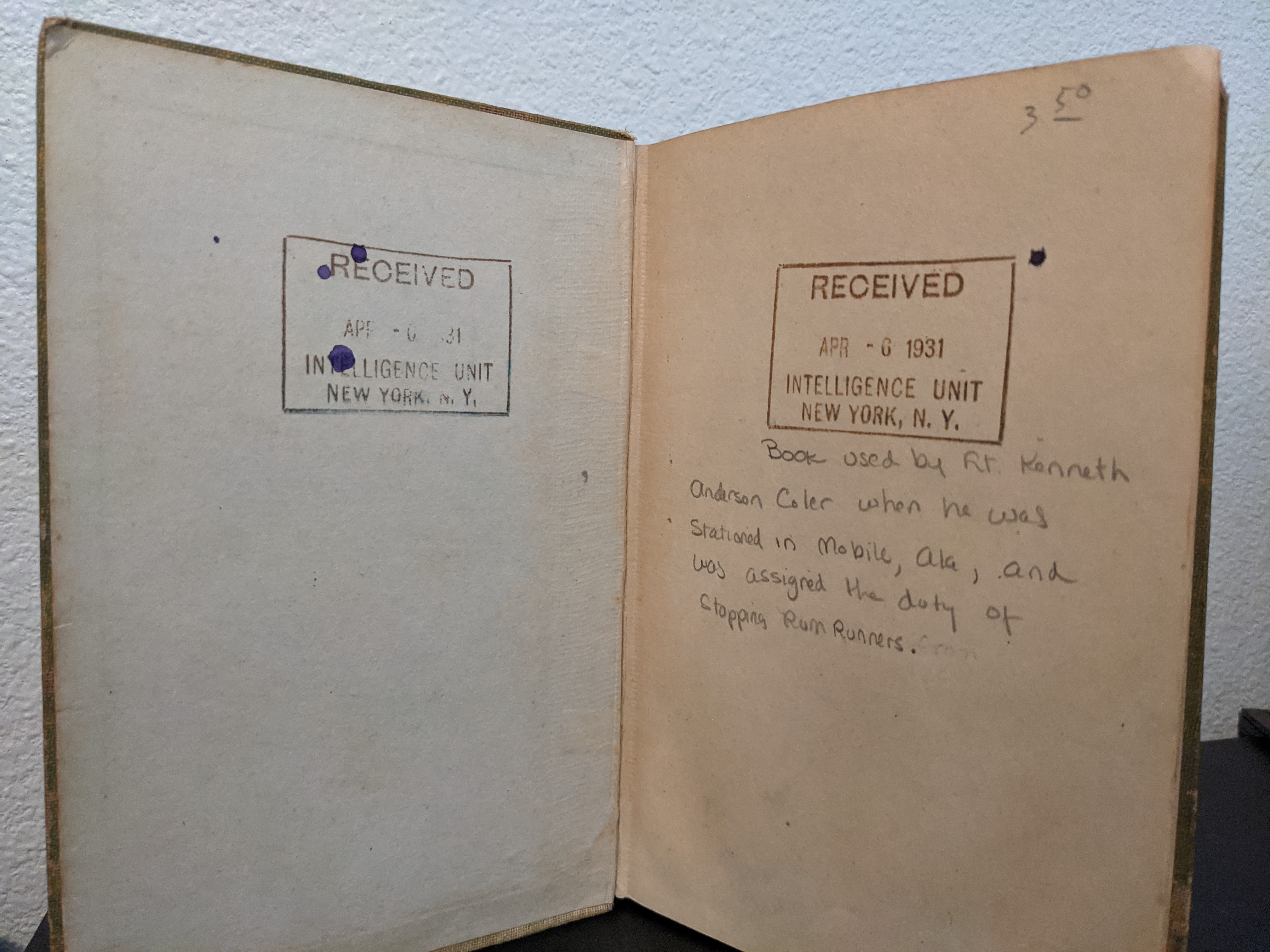

Apparently the book I bought was used by a “Lt. Kenneth Anderson Coler” who was looking for Rum Runner’s in Alabama during prohibition. Unfortunately whoever wrote that in pencil didn’t date it. Maybe it’s this guy? Also apparently sometime after Lt. Coler’s use in Alabama the book got transferred to the “Intelligence Unit” of New York City? Interesting history for this 99 year old book.

Outside of the interesting history, this book launches straight into discussion of dictionary (book) codes by page 35 (It’s about 180 pages long). With an example of “a dictionary of 25,000 numbered words”

Considering we know for a fact that D’A read this book as a reference before/during his own authorship of C&C there’s some really uninspiring quotes in here about dictionary ciphers

Great patience will be required to ferret out the whole of the message…

…in practice such documents are not often found with the numbers written in this straightforward way. Usually the figures are transposed and all sorts of complications interspered

A common method is to rearrange the order of the figures in each group upon a prearranged plan…thus 24133, 21682 … are transformed into 13432, 62182 … the difficulty here is to discover the normal order of the figures in each number, and to restore them to their primitive form … it is a case of bailing the ocean!

Jeesh…this really goes back to my point about this being unsolved due to the obscure/tedious nature of of the possible solution. Considering I just guessed about this book being relevant before I purchased it, it was surprisingly on point with what I hoped it contained, though.

Interestingly, Langie/Macbeth gives us a “Test Message In Cipher” on page 190 and goes on to explain that it will be painful and difficult to solve, and if nobody solves it in “a reasonable time” he’ll publish the solution later. Apparently the solution was provided, since it’s clearly not listed on the “Unsolved Ciphers” wikpedia page and supposedly is a “two-step cipher based upon a Playfair”. I can’t seem to find the actual plaintext, however. Plus the searches are sort of bogged down by Shakespeare references. Then again, the original publishing was in French so maybe I’m just not googling in French good enough.

2022 Update! I Google’d a little harder and managed to get a free download of that annoying Journal website linked above. To summarize, the Macbeth test message was enciphered with a Playfair with the keyword of “J. Macbeth” in the first and fifth lines of the square. Then the message was transposed into Continental Morse Code with dots, dashes, and spaces representing constantans and vowels independently…ah, you know what, here’s the pdf.

One interesting parallel here is that: Langie/Macbeth spend the pages preceding the “test” cipher discussing Playfair, and then provide the reader with an unsolved playfair as a challenge.

In D’A’s C&C he spends the pages preceding his “challenge” cipher discussing Dictionary codes, and then provides the reader with an unsolved cipher as challenge. If D’A was intentionally mirroring the previous work (including a challenge cipher), then he may have also intentionally preceded his cipher with a chapter on the type of cipher that he used (eg. Dictionary/Book Cipher)? Just a Thought.

Also, D’A is almost more known as a cartographer and the author of “Maps” more than he is known as a cryptologist. So isn’t it interestingly that in this book published 17 years prior says in reference to book ciphers

the first thing to do - and it is not easy - is to determine the exact meaning of the two numbers … as when preparing a survey map of a country it is first necessary to calculate with the utmost accuracy the height and distance of two given points, to form a base on which the triangulation of the whole region may be effected…

Transposition of Dictionary Positions

This book got me thinking though, removing the 6,7,8,9,(0) was a bit arbitrary in the sense that we were just guessing, and as D’A himself notes using nulls to throw people off really only works if you’re “in the secret” which we are firmly not. He does spend some time discussing transposition ciphers prior to his dictionary…what if we treat each 5 digit number as a full sequence, but in the wrong order? How many permutations of each letter pair are there, and what happens to the full sequence if the same transpositional rules are applied to each sequence? Which number has the least permutations?

I think the answer to that final question is 92000, the last number in the sequence. Using some quick scripting I found that there’s 20 unique permutations of the number 92000:

00029,00092,00209,00290,00902,00920,02009,02090,02900,09002,09020,09200, 20009,20090,20900,29000,90002,90020,90200,92000

In this case, we can probably ignore anything above 90000 so really the sequence is only 16 unique characters long. We can also use the previous technique of finding the nearest “word” which we know the page/plaintext of. Also, this sequence ends up with some pretty small numbers. It’s not totally unreasonable to figure out words <500.

For example, word 00029 is almost certainly in the “AB” range of words, and its not too hard to count to 29. As always, sort of depends how you count but possibly: abbey, abbot, abbreviate, abdicate, etc. Assuming D’A kept with his military theme, none of these jump out to me. This was just a test though, we have to run the permutation sequence that leads to “00092” (shift all numbers over 2 posistions) to every digit in the sequence and see what makes sense. Before I script this, what I’m really looking for is a higher # of repeat groups. In both book cipher examples given in the two books they find a sequence used several times and map it to a common word as starting point, either “the” or “of” or some other very common word. Maybe we can brute for the permutations that lead to the highest repeat digit group and/or has matches for already “known” plaintext examples from the example in C&C?

Checking all numbers, we find a fairly unsurprising pattern:

| Count | Name | Group |

|---|---|---|

| 26 | 120 | 75628, 28591, … |

| 37 | 60 | 62916, 48164, … |

| 09 | 30 | 74748, 37575, … |

| 06 | 20 | 83828, 81848, … |

| 01 | 10 | 48484 |

Any 5 digit number with 5 unique characters can form a high number of permuatations, 120. As the unique number of letters decrease, the fewer permutations we get. Is this useful? I’m not sure, probaly not. Other than we can narrow down to only 10 dictionary words what word 48484 could be, rather than 120 words for the most “noisy” of the bunch.

So assuming we have a maxium of 120 permutations of certain characters, can we generate all 120 by using this technique?

| A | B | C | D | E | -> | A | B | C | E | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 8 | -> | 7 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 2 |

In this case, treat the cipher as a single column of 5 digit pairs. Then map each first digit with A, second digit with B, etc. Then permuate ABCDE into its 120 versions, and bring each “column” of the underying cipher with

Anyway, a bit of scripting later and here we have them.

Permutation ABCDE (1)

75628 28591 62916 48164 91748 58464 74748 28483 81638 18174

74826 26475 83828 49175 74658 37575 75936 36565 81638 17585

75756 46282 92857 46382 75748 38165 81848 56485 64858 56382

72628 36281 81728 16463 75828 16483 63828 58163 63630 47481

91918 46385 84656 48565 62946 26285 91859 17491 72756 46575

71658 36264 74818 28462 82649 18193 65626 48484 91838 57491

81657 27483 83858 28364 62726 26562 83759 27263 82827 27283

82858 47582 81837 28462 82837 58164 75748 58162 92000

Permutation ABCED (2)

75682 28519 62961 48146 91784 58446 74784 28438 81683 18147

74862 26457 83882 49157 74685 37557 75963 36556 81683 17558

75765 46228 92875 46328 75784 38156 81884 56458 64885 56328

72682 36218 81782 16436 75882 16438 63882 58136 63603 47418

91981 46358 84665 48556 62964 26258 91895 17419 72765 46557

71685 36246 74881 28426 82694 18139 65662 48448 91883 57419

81675 27438 83885 28346 62762 26526 83795 27236 82872 27238

82885 47528 81873 28426 82873 58146 75784 58126 92000

Permutation ABDEC (3)

75286 28915 62169 48641 91487 58644 74487 28834 81386 18741

74268 26754 83288 49751 74586 37755 75369 36655 81386 17855

75567 46822 92578 46823 75487 38651 81488 56854 64588 56823

72286 36812 81287 16634 75288 16834 63288 58631 63306 47814

91189 46853 84566 48655 62469 26852 91598 17914 72567 46755

71586 36642 74188 28624 82496 18931 65266 48844 91388 57914

81576 27834 83588 28643 62267 26625 83597 27632 82278 27832

82588 47825 81378 28624 82378 58641 75487 58621 92000

...

<116 More Permutations>

...

Permutation EDCBA (120)

82657 19582 61926 46184 84719 46485 84747 38482 83618 47181

62847 57462 82838 57194 85647 57573 63957 56563 83618 58571

65757 28264 75829 28364 84757 56183 84818 58465 85846 28365

82627 18263 82718 36461 82857 38461 82836 36185 03636 18474

81919 58364 65648 56584 64926 58262 95819 19471 65727 57564

85617 46263 81847 26482 94628 39181 62656 48484 83819 19475

75618 38472 85838 46382 62726 26562 95738 36272 72828 38272

85828 28574 73818 26482 73828 46185 84757 26185 00029

Unfortunately, I’m not entirely sure why I did this. Sure, this gives me 120 “versions” of the cipher, and maybe 1/120 is the “right” version but I still have to map these to words in the dictionary…and I still don’t want to count. Additionally, this type of transform operation doesn’t actually create new pairings of repeats. So we still don’t have our silver bullet “the” that happens 5 times in the cipher.

Plus, even if there was an “easy” match between the known words from the provided dictionary cipher (I calculated the word distances above)…the re-arranged words barely match up to any known words. I walked through some bad regex and the only “digit grouping” that matches from our “known” words at the top, to D’A cipher in the middle is 55366 which matches “36565” in spot 18. The rest of the “matches” as shown in the image below always have 1 digit too many or too few.

Still a neat way to look at it, I suppose.

Dictionary Method: Page, Line, Letter?

On the page #129 in which D’A mentions the “Dictionary Code Systems”, which is what we’d call a “Book Cipher” he talks about a different way to utilize a book like the Dictionary to encipher text.

One of the ways in which ordinary dictionaries can be used is first to agree on a certain edition…then to only give the number of the page, and the number of the word down the page.. 100612 010417 129108

With 1006, 0104, and 1291 being page numbers and 12, 17, and 08 being words “down the page”

This would decode to

Reunion Berlin Tomorrow

The neat part of this cipher is that Reunion is indeed word ~12 on page 1006, and so on and so forth. So at least we’ve confirmed out dictionary version works?

Let’s try that instead? Using these cipher pages…

75628 28591 ...

But how are these delimited?

- Page Number. Word Number.

- Page Number. Line Number. Word Number

- Page Number. Word Number. Letter Number.

p75.w628 - That can’t be it, we won’t fit 628 words on a page.

p756.w28 - Unlikely as page 756 does not have 28 words on it. You could of course go to the “next page” but then why not just list something like 75704. I think it’s safe to say almost no page in the dictionary will have >20 words on the page unless you get very lucky with a sequence of short definitions.

p7562.w8 - This can’t work since we only have 1500 pages in the dictionary.

p75.l6.w28 - I don’t like this method already because in his example when the page number fell below 1000 he padded with 0’s. Additionally, we’d only be using page 16-92, which seems like a “waste” of the remaining 1400+ pages. Page 75 line #6 word 28 also doesn’t make sense because once you get to line 6 28 words later is another line, so we’ve broken the order once again. Why not list the later line with a smaller word count.

p756.l2.w8 - Still does not abide by the “pad” <1k with 0 method, but it makes a bit more sense. Perhaps Line 2 could be “definiton 2” instead of line? In that case, defintion 2 is “neap” referring to a very low tide, and word 8 of that is “In”..maybe. Depends how you count. I suppose I can’t discount this entirely, the cipher could start with the word “In…”

p75.w6.l62 & p75.w62.l8 - Neither of these make much sense since again, we’d be ignoring 1400 pages of text, and finding letter 62 of “word 6” is impossible, additionally letter 8 of the 62nd word seems like a frustratingly bad code.

p756.w2.l8 - The second word on page 756 is once again “neap” and if we go to letter 8 we find uh… “a. & n., & v.t. &i. N. -tide or n., tide” See…these deifnitons are often trailed with a long sequence of definitions for if its a noun, etc. Do you count that? Letter 8 is “n” if you ignore all of that and focus on the actual definition of “tide soon after the moon’s first & third quarters…”

Needless to say, there’s a lot of different ways you can mix this up. There are some limits, like page number. But this is sort of an infinite game without discussing in advance how to process the numbers. Maybe it’s backwards and lists the word number, the deftinion number, then page number in acsending order instead of decending? I think it’s safe to assume one of the numbers would be page number, but what after that? Line number? Letter/Character Number? Word Number” Number of bolded definitions? Maybe it’s not even the whole word referenced, maybe it just wants you to take the first letter? Or the last…see, if you and your spy friend agree on a very specific sequence like

“Page.Definition #.Word# - always use the 1st letter if its in column 1, but use the last letter of that word if its in column 2…”

We’d never figure it out, and without a clue to that it would be pretty well impossible…maybe.

Page, Line, Letter: The Book Itself

Maybe we don’t use a dictionary, but rather the book itself?

| Page Number | Line Number | Letter Number |

|---|---|---|

| 75 | 6 | 28 |

| 28 | 5 | 91 |

| 92 | 0 | 00 |

Page 75 is not entirely text. It has “Boy Scout Signs” injected halfway through the page, with a sub-title and diagrams. Do you count sub titles as a line? How about diagrams that unevenly adjust page spacing? Maybe its

If you treat every “Line” as a line, title or not, line #6 is “Australia” … which does not have 28 letters to pick from. Maybe we ignotre the “Page Title”, that pushes line #6 to “Boy Scout Signs”…that also doesn’t have 28 letters to pick from. If we ignotre that line, since its a title we finally have something workable:

The four principal scout signs derived by Lord

Which condensed to count the letters

ThefourprincipalscoutsignsderivedbyLord

Letter 28 is ‘e’ …but there were a lot of assumptions about titles to arrive at this letter.

Let’s check the next page #28…and its even worse. How do you even parse this by Line # and Letter?

Okay, maybe page 92? Wait, what’s line #0? What’s Character #0? Is the code 0 indexed or should I start count from 1? If I count from 0, then suddenly the first solution isn’t ‘e’ it’s ‘r’…

Perhaps the book isn’t the key. Seems too sloppy, too much guess work, and this book has non-standard formatting on nearly ever page.

However there are a lot of ways to slice the five digit number:

- Page, Line, Letter

- 75,6,28 – The only “Valid” split I can see.

- 7,5,628 – Well…we certainly won’t find lines with 628 letters on them.

- 7,56,28 – Unfortunately most pages are only ~30 lines long, so not probable.

- 7,562,8 – Breaks reason with >30 line numbers.

- 75,62,8 – Breaks reason with >30 line numbers.

So any split where the first digit is <7 is unreasonable to apply.

Example: 28591 page 2 isn’t numbered, and if it were, it’s an entirely blank page.

So none of the alternative splits make much sense, either?

The Book Itself - “Hidden Alphabet”

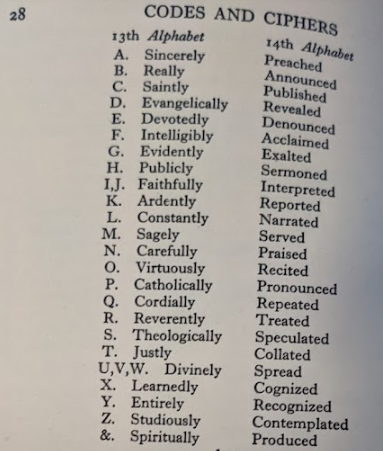

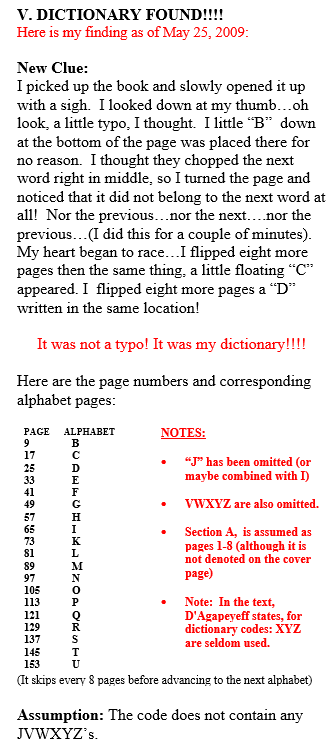

When I was flipping through the book I noticed small upper case letters on certain pages. After some investigation, I discovered they were about every 8 pages. I did some research, and these are known as Signature Marks. These marks are related to a now outdated bookbinding technique that ensured the pages were bound in the right section/order when building (binding?) the book. This is also known as “collating” or “designation marks” in bookmaking, apparently.

Sadly, I found this person’s website later in my research. They have a whole word document from 2009 where they apparently got very excited over the discovery of the “little alphabet.” As far as I can tell, they never figured out what the Signature Marks are.

Although I do find it interesting that the collation does not include “J” ? And I give the guy in 2009 some credit, early substitution ciphers like playfair usually did combine I and J.

Each section has a different signature, and when letters are used for identification, as is the usual practice, they progress in alphabetical order, with J, V, and W usually omitted to avoid confusion, although their exclusion does have an historical basis, in that manuscripts and early printed books were usually in Latin, in which I stands for both I and J, V for both U and V, and there is no W.

I don’t think this is the solution to the cipher, nor the key. I don’t think D’A would have had control over the way Oxford published the book. I also don’t think D’A would have even thought twice about the signature mark being in the book, as he wasn’t in the printing industry by trade.

Anyway, this was a waste of time. I guess I learned some random book trivia? And so did you if you bothered reading this

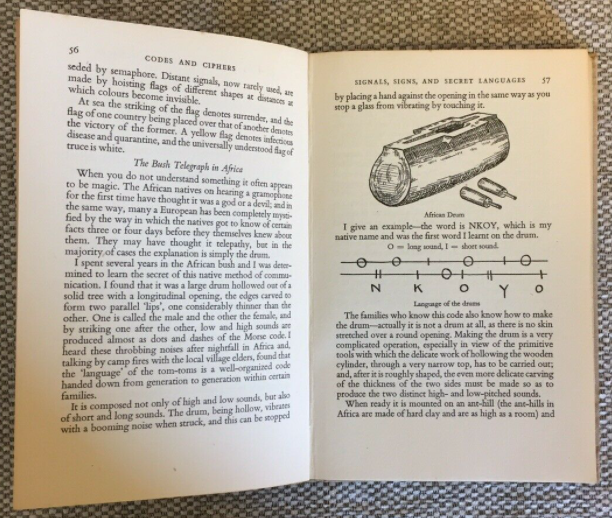

The Book Itself - 1949 Edition

The cipher, unchanged, is included in the 1949 edition of the book. However, the 1949 edition is apparently slightly larger. Thus, the page numbers don’t align anyway.

Here’s a screenshot of page 57 from a 1949 edition I found listed on ebay.

The “African Drum” illistration and language graphic is on page 53 of the 1939 edition. We’re way off. The book is likely not the key.

I suppose you could argue that D’A had the cipher removed from the next print run of the book for this exact reason. “Oh dear, its not possible anymore!” … I’m guessing not.

I also bought a 1952 edition (ebay), the one where the cipher is removed, and confirmed that once again, the page numbers shifted. How fun.

Other Approaches

Coincidences in Text Formatting

In writing, often times framing is very important. One framing technique is known as “bookending” or simply a “bookended story.” These are stories where the very beginning of a work is paralleled in the ending to create a sense of closure, or a loop that has a satisfying resolution that harkens back to how the story began.

So, I’m probably in a rabbit hole here, but the cipher in the original text is at the very end of the book, so what’s at the beginning?

Why did this catch my eye at all? Well first, it’s suspiciously square. That sounds stupid.

It’s 8 rows with a sentence that happens to have 10 words? Unfortunately, this pattern changes between 8-5 words per sentence, and depends how you want to count words like “in-terest”,”co-operation”,”through-out”…So maybe this is just a coincidence of monospace font styling. 52 words total? Either way, it caught my eye for a few minutes. It felt like certain words were sort of arbitrarily hyphenated to the next line to fit a particular formatting.

Why not just change the font size or use slightly wider margins like they did in the 1952 edition where they removed the cipher? Oh…okay, not falling for that mental trap. The removal has nothing to do with the reformatting of the dedication page. The removal has nothing to do with the reformatting of the dedication page. The removal has nothing to do with the reformatting of the dedication page.

Joking aside, I don’t presently think there’s anything to this block of text. Plus, much like the dictionary “forgotten” rant I had earlier, why would D’A have forgotten that he used his dedication page as the key? Sadly I was able to find no information on the Internet about “Geoffrey and Marjory Cass” or “Rachel Wood” for whoever they may have been to D’A.

Page 113: Army Cipher

This page discusses an army signal cipher It breaks it up into “sets of five” set apart by / to be grouped. Additionally, the messages ends in AAA

One should note that AAA signifies the end of the message.

This is similar to the cipher which has groups of 5, and it ends in 000 (AAA). Is it possible one of the repeating characters in the groups of 5 represents a delineation slash?

I used the idea on page 113 to break up the text on possible repeating delimiters (Eg. /). Unfortunately, the average length of a word in English is only 5 letters. Unsurprisingly, the sequence with the highest frequency, 81, produced the smallest word lengths – but even so the length is 17! Way beyond the expected value produced by English.

| Delimiter | Words | Avg. Word Length | Max Word Length | Min Word Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | 2 | 196 | 392 | 1 |

| 04 | 2 | 196 | 199 | 194 |

| 62 | 18 | 20 | 62 | 2 |

| 63 | 13 | 29 | 130 | 6 |

| 64 | 17 | 21 | 58 | 2 |

| 65 | 12 | 31 | 82 | 4 |

| 71 | 2 | 196 | 250 | 143 |

| 72 | 10 | 38 | 150 | 6 |

| 74 | 15 | 24 | 74 | 6 |

| 75 | 18 | 20 | 82 | 2 |

| 81 | 21 | 17 | 62 | 2 |

| 82 | 18 | 20 | 80 | 4 |

| 83 | 16 | 23 | 74 | 4 |

| 84 | 12 | 31 | 70 | 4 |

| 85 | 18 | 20 | 72 | 2 |

| 91 | 13 | 29 | 132 | 2 |

| 92 | 4 | 97 | 222 | 3 |

| 93 | 3 | 130 | 194 | 82 |

| 94 | 2 | 196 | 222 | 171 |

A Rabbit Hole of Playfair

Is it coincidence that Mansfield’s Solutions to Codes & Ciphers and D’A’s Codes and Ciphers features what is essentially a Wheatstone Cryptograph on the cover? I suppose not, since “cipher disks” predate Mr. Wheatsone by a few hundred years.

Still, it could be a vague homage to Wheastone who also invented the much more useful Playfair system. Is the cover of this novel a round about hint to utilize Wheastone methods? Eg. Playfar? Probably not, but regardless it seems fair to conclude that playfair could be part of the solution.

This is even more interesting when you consider D’A’s role in WWI and the widespread use of Playfair and ADFGX/ADFGVX ciphers in that conflict.

One potential solution I think is worth playing with is a hybrid polyibus and playfair cipher.

More Old Books & Other Misc Sources…

After I had found it in digital form on Archive.org it got me thinking about other books that may have been published before the D’A cipher in 1939 that had been digitized…

One interesting thing about the idea of looking for hints in recently digitized text from the 1920s and 1930s is that it is extremely unlikely that anyone has really read over these antiquated version of cryptography in quite some time. Additionally, nobody really had “access” to many of these texts until they were digitized (typically soemtime after 2015).

To Google Books we go!

Popular Mechanics There’s a fun article from a 1926 Popular Mechanics (Vol. 46, No. 4?) titled “The Magic Lure of Ciphers”.

Although I wish I could say this article gave me some magic lightbulb idea for the D’A cipher it ultimately did not. But, it does include some interesting and direct references from Col. George Fabyan as well.

Elements of Cryptanalysis - United States. War Department (1923). This was actually a very interesting read that certainly pre-dated the D’A cipher by 16 years.

U.S. Army FM-34-40-2, Basic Crypt-Analysis - The US Army at it again with a manual too long to read, but full of great info on basic ciphers.

References & Additional Reading

Wikipedia

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D%27Agapeyeff_cipher

Tools

- https://regexr.com/

- https://sites.google.com/site/cryptocrackprogram

- Excel, Powershell, Python, Google

Life Notes on Alexander D’Agapeyeff